For English, please scroll down

Laura van Grinsven: 'Gift-geven' in: Metropolis M #2 2022

Dora Garcia and guests, EXILE, 2012 tot nu, geschreven brieven en drukwerk gestuurd aan instellingen die haar werk tentoonstellen, presentatie Kunstinstituut Melly, Rotterdam, 2018, courtesy de kunstenaar en Ellen de Bruijne Projects, Amsterdam

Laura van Grinsven: 'Gift-giving' in: Metropolis M #2 2022

In the current neoliberal era, the art world has become a rigid structure in which critical art is exhibited but not internalized. The artist's name seems more important than the intended effect of the artwork. Laura van Grinsven sees a hopeful alternative in the practice of gift-giving, a reciprocal understanding of art that strives for collective autonomy.

By Laura van Grinsven

The production and exhibition of art usually happens in a continual dynamic of creating, showing, selling, and removing. What does this cycle serve? Recognition and position within the art world? Exhibitions in prestigious institutions? Raving reviews? All these motivations are, in many cases, for the ego of the artist or curator and on in service of the self-confirmation of the art world. It is an internal dynamic, caught in the trap of neoliberalism and (going hand in hand) the celebration of hyper-individualism. Could there be an alternative?

I see a possible alternative in the concept ‘gift’. Viewing art as an act of giving can provide a sense of direction. It can change motivations from making something solely for recognition in the art world and for oneself, into directing the work to another cause. Giving enables the artist to reflect on where and for whom or what the work might be. Giving means breaking free from the chains of the current art circuit, trade, and also from the white cube and neoliberal art production. A good gift is always a collective act within a community, thus putting an end to the ego-artist. A gift is always situated and will have an effect within that situation.

The focus in this piece is not so much on the economic principles of the gift, but on the discursive aspect, and the infrastructures that this discourse implies. Since the gift in my argument is not a thing but an art practice that aligns with a situation, I can better use a verb: gift-giving.[1] Gift-giving places no demands on the work itself. It mostly provides a direction and opens up a possible alternative infrastructure for art. I see a discourse in terms of gift-giving as a potentially alternative way of thinking about art, thus generating other, more social, practices with the idea that thinking differently can initiate a shift in actions.

To define art as gift-giving, I begin my story in the exhibition space, in the white cube. In our society, art is usually to be found there. We take this space for granted. And not only by looking from the outside in, but also the other way around, for example by exhibition-makers. Even artists often subconsciously have the white cube in mind as the final location and mode for their work. The white cube was, for years, an exclusive boys' club, with its own geographic and gendered language, history, valuation system, meaning, and discourse. Nowadays, others can also join, and there are various voices and stories to be heard. The old rules, however, usually still apply.[2]

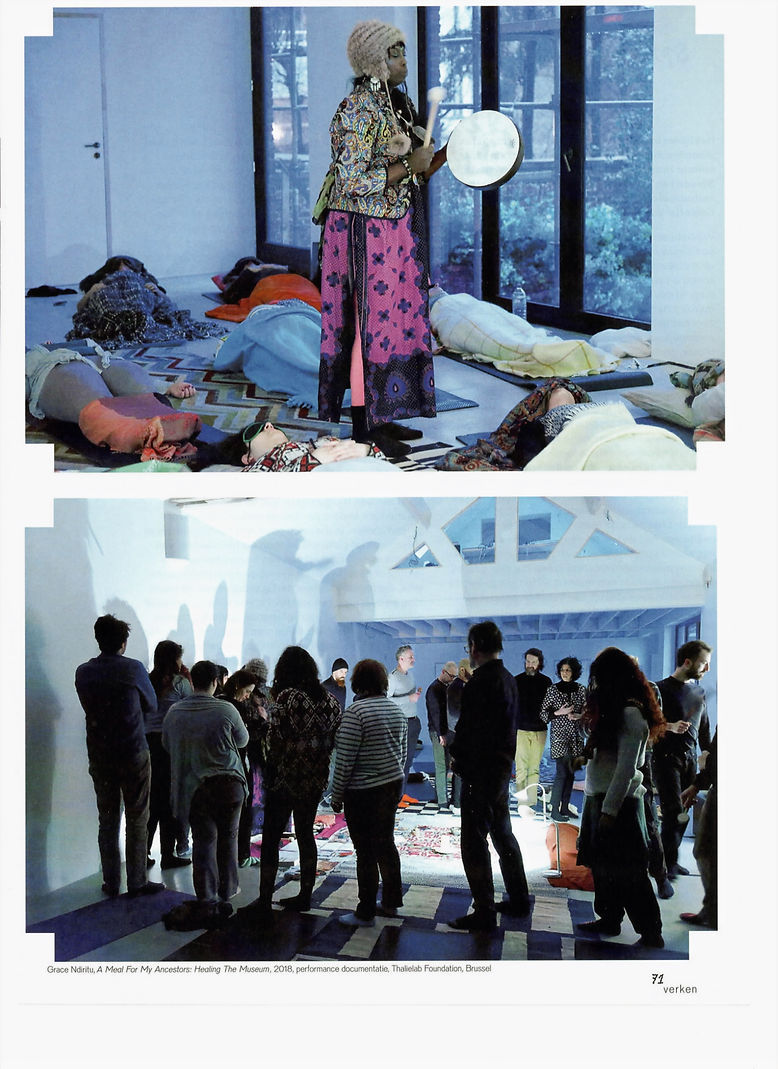

Theoretical and artistic practices have long tried to change the structures of these institutions. The intentions of art as gift-giving are not new. For example, Jayson Musson parodies the Western hermetic discourse with his character Hennessy Youngman in the YouTube series 'Art Thoughtz'; Dora García opened the exhibition space to others who would normally have no access in her work 'Exile' (2012 - present); and Grace Ndiritu sought to introduce different customs into the structures of the museum by performing shamanic rituals in 'Healing the Museum' (2012 - present). At first, all these practices show that something is wrong with the art institution. Moreover, there are also elements of gift-giving to be found: Musson gives air to the heavy structures by mocking them, García gives her own space to others, Ndiritu gives collective energy and solidarity.

However, the infrastructures and underlying discourse are not really penetrated by these practices. The art institution effortlessly incorporates the critique as a new art form, absorbs it, and renders it harmless. Critical artists are made members of the club, the rules of which remain intact. The delivered critique is encapsulated in the white cube and dismantled, and the artist’s name is used as promotional material. In the end the membership and that name stick, and not the function of the artwork. Despite the idealistic intentions, the above practices are effectively swallowed up by the workings of the current art discourse. What I propose is to redefine gift-giving, so that a sustainable alternative infrastructure can emerge.

You Scratch My Back

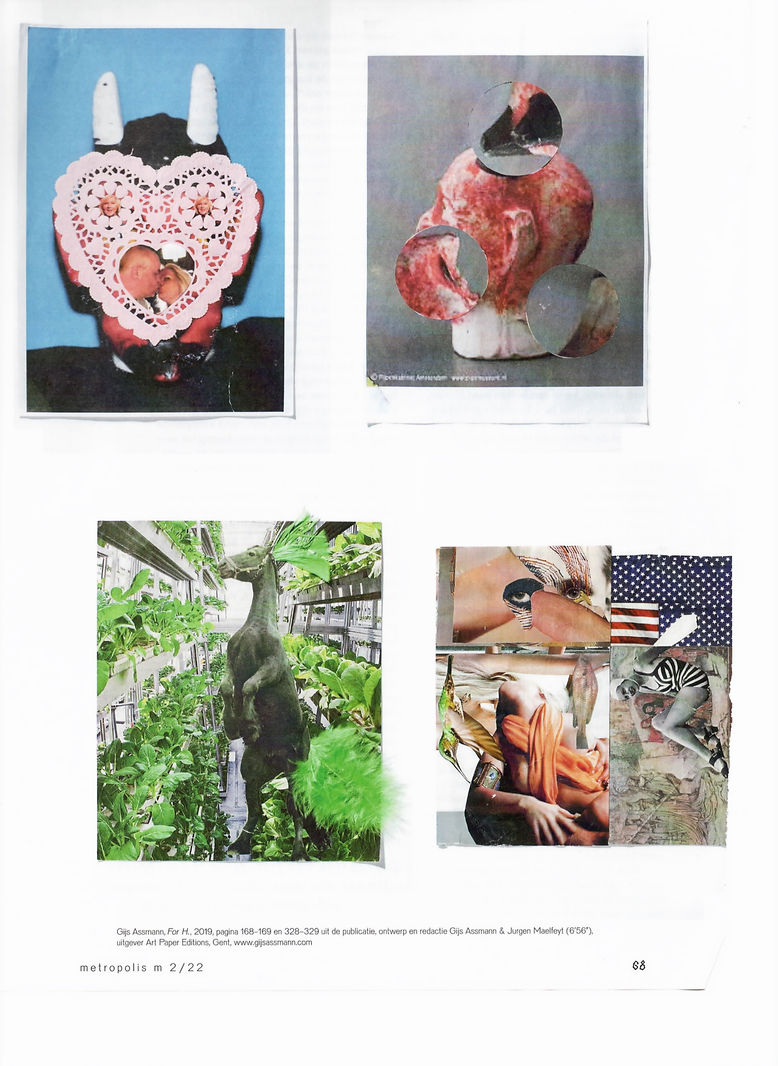

From the very beginning of their relationship to the present day, Gijs Assmann sends his partner H. a collage by post every day, with a personal text on the back. This collection now fills several dozen boxes. Every morning, before going into his studio, making a collage is a ritual act in which he forces himself to be conscious and reflect on himself and his loved once’s. Each collage is proof of his dedication to the relationship, and every day, once the postman has come, there’s another confession on H.'s doormat. The cards are a romantic gesture and, at the same time, a trap, a never-ending demand for recognition and pressure for the other to make the same commitment and reflection. Sometimes, the unopened envelopes with collages pile up in her house.

In anthropological and philosophical studies, the gift is mostly interpreted to establish a relationship of dependency, make the receiver dependent on the giver. Under the cloak of love, the giver assumes a certain kind of reciprocity. Giving to the poor, volunteering, emotional support, and even teaching can be understood this way.[3]

Anthropologist Elizabeth A. Povinelli points out in her article 'Routes/Worlds' (2011) that we interpret situations where there is an act of giving far too one-dimensionally. The focus is solely on the giver, the receiver, and the gift itself, as if this exchange exists in a vacuum. It is forgotten that giving is not a fixed, reciprocal action of giving and receiving, but a tangled web of actions. A gift always occurs within a context, a specific situation, and a community. Bringing a bottle of wine to a party at the home of Muslim friends is a misplaced gift. Thus, the gift is not just about the giver and the receiver, but about an entire community and their customs and values, and being involved in that.

Assmann's gift cannot simply be understood as a collection of collages. Each day, his new gift asks for an acceptance, not only by receiving the collages but also of a certain dynamic and engagement within the relationship itself. Accepting the gift is not neutral and brings responsibility. And there’s a risk – one day, H. may decide not to accept the gift anymore. There is a compulsory reciprocity at play, where the receiver cannot be passive by definition. Whether something is received or not, but also the way in which this happens, is a crucial element of gift-giving.

Gift-giving is a collective practice and breaks with another syndrome the art world suffers from, namely the idea of the artist-as-an-island. In gift-giving, more than one party is involved by definition, just as Assmann cannot be considered the sole author of his work. The circumstances of the relationship with H. and the focus on her reaction, also shape the outcome of the work, it shapes what the work is.

For her exhibition 'A Daily Practice' (2020) at the Van Abbemuseum, Yael Davids made the collective origins and building blocks of her practice explicit by bringing together works by different artists, each of whom filled a gap in the collection. And in the exhibition '5 Weeks, 25 Days, 175 Hours' (2016) at Chisenhale Gallery in London, Maria Eichhorn decided to give the staff of the institution time off, to draw attention on all the (their) labor that is required to organize an exhibition. It is interesting that, in both these tributes, the artist continues to remain the sole author: Davids' work never merges with the work of her sources, and not the museum staff, but Maria Eichhorn remains the author of the exhibition. And although the work came into being by the help of many hands, those who contribute are often reduced to collaborators, material, or subjects in the description. Thus, everything is in service of the work and the artist’s name. This once again shows the hegemonic position of the art institution. The name is the currency of the artist, for new commissions, reviews, and sales. In the practice of gift-giving the aspiration lies in the relinquishment of the artist as the sole author and embracing the collective nature of art practices.

Reciprocity

Gift-giving is a collective act of reciprocity. In fact, the world we live in is already a gift, no matter how much Western thinking focuses on consumption, use, and appropriation, writes Robin Wall Kimmerer in her book 'Braiding Sweetgrass' (2013). A sustainable attitude to existing, would be to consider that what is given – oxygen, food, warmth – as a gift for which conscious gratitude is required. Seeing the world as a gift also brings responsibility. In the case of gift-giving, this is the trap of reciprocity. Is that so bad? The hyper-individualistic culture, in which everyone thinks of themselves and shifts responsibility onto others, is under pressure. In our drive for self-determination, we have forgotten to think about each other and our planet. Kimmerer emphasizes that, after becoming aware of the gift of life and adopting an attitude of gratitude, the question of reciprocity can be asked: What can I do? What can I give? It is about considering what good you could do, for whom, and where.

A gift is a very specific form of care-giving, argues Maria Puig de la Bellacasa. In her book 'Matters of Care' (2017), she explains that in order to give someone a good gift, you must be aware of the circumstances of that gift. What effect does the gift have? How can it be used? How is it interpreted? Can it mean something? Is it even wanted? As a giver, something is at stake. A good gift is always political and ethical. Giving is a risk. It requires constant adjustment, attention, consultation, and getting your hands dirty. Care is messy, giving is messy, says Puig de la Bellacasa. The receiver of the gift is not a passive being. The gift can be refused. True giving (with care) requires you to have empathy with the other without pretending to be part of a group when you are not. It is important to know from within how the other can receive without losing their self-worth, without losing their agency. You cannot ever speak for the other, nor decide for them. What is needed is caring 'for' and not caring 'about', which has more to do with our own ego. Caring 'about' does not require any action, as caring 'for' means cultivating an awareness of a specific situation, offering care and attention before the gift can be given. Gift-giving also involves looking critically at yourself. Where do I stand, and what can I contribute? Care and attention are needed to ethically bring the gift you have to offer into the situation.

In the context of art, I want to emphasize here that a gift doesn’t have to solve anything. The resistance and politics lie in the new infrastructure that giving offers, more than in the topic or work itself. Art as gift-giving can be anything and can happen anywhere. Gift-giving doesn’t mean a new form of communism: it does it call for sameness, but rather an attitude of gratitude and the question: what can I individually, with my expertise and experiences, contribute? Gift-giving is precisely about diversity, about all different practices, but with the understanding that we must and can only achieve such a gift-structure together.[4] I would call all this 'collective autonomy'.

It is vital to realize that autonomy in relation to an existing discourse, to a given infrastructure, can never be achieved by an individual; it can only happen collectively. Collective autonomy is the freedom gained by working together. Collectivity works in gift-giving on different levels. First, in any given situation, others are involved, such as the staff at the Chisenhale Gallery in Eichhorn’s work and H., Assmann's partner. Second, collective work is an escape from the artist’s ego. And third, perhaps most importantly: we cannot do it alone.

Laura van Grinsven is an art historian and philosopher.

With thanks to Miriam van Rijsingen and Vincent Vulsma, Gijs Assmann and Johan Wagenaar, Students of the Posthuman working group, and colleagues at BEAR

Notes:

[1] Art as a Gift is an established topic. Lewis Hyde wrote the famous book 'The Gift', in which he argues that all art is a gift and holds a value that cannot be expressed in monetary terms. Hyde assigns a metaphysical power to art, which he calls the gift. The artist also creates the work with a gift, the moment in the making when control is lost, and the work transcends the artist intentions. This is very different from the Gift-giving that I have in mind. Recently, anthropologist Roger Sansi published 'Art, Anthropology, and the Gift' (2014), in which he discusses the social factor of participatory art as a gift. Although many aspects of participatory art can be seen through the lens of Gift-giving, there is a clear difference. In participatory art, the duration, attention, and the role of the artist remain exactly as they are within the art institution and infrastructures. A project has a defined duration and is then ‘taken down’, disappearing from the lives of the participants. The participants do not take on a true, sustainable responsibility for the gift, nor do they gain a position as co-authors.

[2] There is no shortage of critique of the white cube. A key text is 'Inside the White Cube' by Brian O'Doherty (1986), in which he demonstrates that it is not a neutral space but also an aesthetic object that the artist can engage with. A more recent critique comes from Elena Filipovic: 'The Global White Cube' (2005). She declares off-site exhibitions, such as Manifesta, as a potential escape from the sterile environment of the white cube and as a way to enhance accessibility for a more diverse audience.

[3] Important studies on the gift are mostly anthropological and philosophical. The key text is 'The Gift' (1925) by Marcel Mauss and the debate on the economy of gift exchange with his contemporary Bronisław Malinowski. According to Mauss, gifts are binding factors in a society, which is why in many gift cultures, there is a prohibition against hoarding. Jacques Derrida, in turn, offers a negative interpretation of the gift, viewing it solely through the economic and political motives of the giver. He argues that a selfless gift cannot exist, except perhaps in a state of madness. Pierre Bourdieu also sees gifts as measurable interests that involve a clear strategic goal through the implicit reciprocity that underlies the gift.

[4] Inspired by Rosi Braidotti's famous saying: "We are all in this together, but we are not one and the same", in Posthuman Knowledge (2019).